Two weeks ago, I spoke with Zachary Irwin and James Lacombe of Opaque Industries about their upcoming tabletop fantasy roleplaying game Song of Swords, which is now being funded on Kickstarter. In Part I of the interview, which you may read here, we discussed how historical martial arts influenced Song of Swords’s distinctive combat system. This, the second part, concerns the historical and mythological influences from which the setting of Song of Swords, the Tattered Realms, sprang.

Two weeks ago, I spoke with Zachary Irwin and James Lacombe of Opaque Industries about their upcoming tabletop fantasy roleplaying game Song of Swords, which is now being funded on Kickstarter. In Part I of the interview, which you may read here, we discussed how historical martial arts influenced Song of Swords’s distinctive combat system. This, the second part, concerns the historical and mythological influences from which the setting of Song of Swords, the Tattered Realms, sprang.

As before, the transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: I’m curious about how actual history affected the setting [of Song of Swords]. What did you keep from history? What was inspired by it? What did you change?

Zach: This setting is really James’s baby, so I’m going to let him answer it.

James: When I was growing up, back in the aughts and the nineties… you never got the impression people who read fantasy and wrote for these games or books or shows actually cared about the history of the world, or particularly about the history of parts of Europe that weren’t England. It always seems to be medieval fantasy. Everyone has a British accent. Everyone is this stereotype of Anglo-Saxon chivalry, whether it’s portrayed positively or negatively. It always felt pretty much the same. And you know, that’s cool. Anglo-Saxon history is cool. The point is: there’s more than that. There’s Germany. There’s central Europe. There’s Poland, Eastern Europe, and Hungary. Italy and Spain. Russia. The steppes. There’s the Balkans, Bosnia, and all these little kingdoms that never see fantasy set in. A big focus of the setting of Song of Swords, which is Tattered Realms, was to bring the focus in more to the heart of Europe, to [show] a different kind of fantasy and medieval world.

James (con’t): The British view of history… it’s very different from Saxony, or Bavarian history, where you’re surrounded on all sides by other kingdoms. There’s no ocean keeping the French away from you. And that [is reflected in] their history, their mythology, the way that their culture worked and the forms their feudalism took. Most fantasy media don’t try to portray that. You get a few, on occasion, that do it pretty well. You get The Witcher. The Witcher knocked that out of the park, because it was written by a Polish guy. It gave a very good view of Central and Eastern European pathos when it comes to remembering medieval and Renaissance history. Where we were coming from with the worldbuilding was: “Let’s give a changed, a little bit of a tongue-in-cheek in some places, portrayal of, essentially, Europe.” In a lot of places, it’s a “What if?” Europe. That’s always fun.

Q: What are the differences in mentality, mythology and feudalism between, say, Central Europe, France and whatnot? How does that translate into different fantasy?

James: Here’s a good example, which is in… I believe it was the 14th century, but it was probably a little earlier than that… Yeah, it was in the 13th: the Magna Carta was signed in the Kingdom of England. This was an agreement, essentially, made at gunpoint (or swordpoint rather) between the nobles of the Kingdom of England and King. I believe it was Prince John at the time, who everyone hates from Robin Hood. This was essentially a constitution, more or less, that granted certain rights to the nobles that would not be infringed upon by the King. And this was a huge step forward. A lot of people don’t understand just how significant it was for a government to limit the top echelons of its power in a feudal society. It almost never happened. Meanwhile, in the Holy Roman Empire, there was no such consistent measure. There was no Magna Carta. Instead, there were twelve courts of law and eighty kingdoms and principalities, duchies and whatever else–precincts and all this stuff, and the rule of law was never really consistent. So the myth of the noble King, the idea of a rightful King who holds the throne, and has certain responsibilities, and has almost this mystical aura about him is very much an Anglo-Saxon thing, I think. I don’t think you see that too much in the Holy Roman Empire. You see a lot in old Germanic mythology, going back, obviously reaching back to that Karl the Great guy, and that sort of thing. But you don’t see it so much in that time period in particular, whereas the romanticization of feudalism was kind of a thing in British culture for a long time. That plays a lot on how people perceive the world around us. If you think that the institution of the King, of the monarchy, is in a way holy, If you believe in the Divine Right of Kings, how does that affect how you look at monsters? If you think that your king is literally descended from St. George the Dragon Slayer, then reasonably dragons must have some kind of beef with kings (which I suspect is probably why they keep kidnapping princesses). But if you look at Germanic mythology… it’s a little bit cruel to say they were more dire for much of their history, but it’s kind of true. In the Holy Roman Empire, and Germany and Poland to an extent, people had a rough time throughout the centuries. A lot of their mythology is really dark as a result. German fairy tales are famously horrifying. Famously grim stories—as recorded by the Brothers Grimm, now that I think about it.

Q: Quite likely where we got the word from.

James: Yeah, it’d make sense. But you understand that the perspective, the surroundings of a people tend to color their mythology. And so you can’t get the same kind of fantasy just by showing one culture. It helps if you can move over to central Europe, or at least just continental Europe somewhere.

Q: Is that what informs the grittiness in the Song of Swords setting? If you’re looking for more a central European vibe, then it seems that grittiness comes naturally out of that, those stories from Germany. Of course, if you’re not quite in Germany… I mean, even though Bram Stoker altered [the concept of a vampire], [his] vampires are partly derived from Romanian mythology.

James: From Slavic folklore, definitely. No question about that.

Q; And [that], from what I’ve heard of it, sounds absolutely dark. You seem to have some very, very gruesome monsters in there. The only comparable ones I’ve heard of are some from Indonesian mythology.

Zach: [chuckles] I’ll say that in Romania, Vlad the Impaler is a hero. So that should tell you everything you need to know.

[laughter]

Zach: On that note, I’ll also say that it’s hard to be realistic without being gritty.

James: That’s true. We say “grim” and “gritty” in terms of how the violence is. But I wouldn’t say that this is a very cynical game. We’re not trying to ruin anyone’s fun in fantasy here. A lot of really cynical depictions of the world [in] fantasy are really trying to ruin your fun. They don’t want you to enjoy the idea of going around, fighting bad guys, being a knight, and taking down invaders and stuff like that. They want you to feel depressed about how crummy things were in the medieval period, and that’s no fun. No one wants that. We should be looking back at the past, and all that cool stuff that happened that we’ll never get to experience, and glorify that a little bit. And to play it up, to play up the good parts. That’s what this is. It’s entertainment, you know? The game is violent. It’s very easy to die. But that is intended to make your victory feel, or taste sweeter, so to speak.

Zach: It’s all about risk versus reward for us. We have that skewed a lot more than most games do. Because when people do something heroic, they give all for the quest, or protecting the village or whatever they think is in their character’s nature, they really want to feel like it has a lot more clout than it might in Dungeons and Dragons.

Q: So it’s more for narrative, or enjoyment purposes, rather than to reflect the mythos of a particular culture.

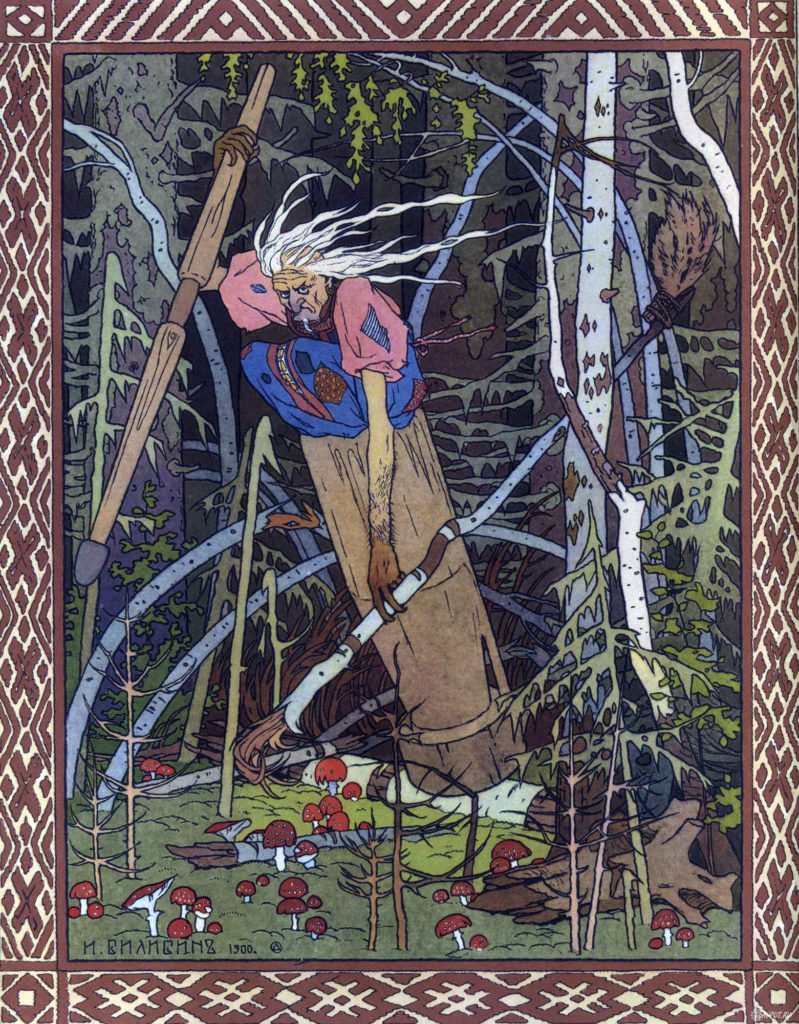

James: I’d say so. Even in the most grim and brutal of Slavic fairy tales, they still have unstoppable heroes.

[chuckling]

James: You know? You have Alexander Nevsky effectively made a mythological figure after he defeated the Teutonic Order at the Battle of the Ice. And if there’s anyone more depressing in the world than the Russians, I haven’t found them yet.

[laughter]

James: But they still had their own heroes, no kidding.

Q: How does magic or anything mythological in the setting work, and what specific myths did you draw up on for the system?

Zach: I think it’d probably be a good idea to give an overview of the mythos and then the magic. What do you think, James?

James: Wooh… oh man, this is a deep subject. When we were going into the idea of making this setting, one thing we wanted to avoid was the stereotypical fantasy mythology. You know, you have a pantheon, you have a “God of X” and a “God of Y,” and a “God of Z” and a “God of E to G,” and just a bazillion gods: a god for every occasion. Everyone worships a different god, and you really don’t divide it up by culture so much. The gods are just all objective, and everyone worships a different one, and they’re all cool with that. That’s appealing to D&D and modern sensibilities. But that certainly has never been the case in Europe. Except, maybe, in the Roman Empire, for a brief time, was it that open. It really kills a lot of the interest of a medieval, European-esque setting, where half of the fun of the history of that period was how messed up the religious scene was. So the mythology and the cosmology of the setting is meant to be evocative of that. It isn’t just a straight copy of Christianity and Islam, of Judaism and all that. It’s different. [But] we did draw very heavily from Judeo-Christian mythology for a lot of what’s going on, and I will not explain because part of the fun of the game [is] trying to figure out what the heck is actually going on in the stars of this world. The gods must be crazy—what are they doing? Figuring that out is half the fun. A few of our fans are very dedicated to trying to figure that out. Essentially, there are two principal deities that are well-known. In Western Vosca and Central/Eastern Vosca, Karthack, and the desert to the southeast, you have Genosus, which is the Sun God. All of his worshippers are in the West right now, and that represents Europe, per se. So you have Genosism, which is sort of a Catholic-esque religion built around the sun god Genosus. There’s an eclipse every thirty days, and it is believed that the Sun God comes down from the sky down to his temple, where he chills for a day every month. But while he’s gone, dark forces can enter the world and start messing things up. So he has to come back out and drive them out. But no-one ever sees that. They just see the sun go out, and then monsters invade. Then they hole up in their towns for a night, and then wait for stuff to go away so they can go out and get back to work. Then there’s the Bocanadessia, the moon goddess of Karthack. And so, this deity was, according to legend, lured down to Earth and captured by the Karthacks. Their god-king was determined to prove his mastery over the cosmos, so he kidnapped the moon, basically. And then bad things started happening. People revolted against the king, cast him out, and then released the moon goddess, who then agreed to rule them through the medium of another god king, who’d be her husband. So these are the dominant religions, now. How true either of them actually are is not really knowable, unless you’re going to break into the royal palace of Karthack and see if they have a moon goddess hidden in there somewhere. Which, granted, would be a cool adventure. Or if you went to the solar temple of Genosus, named after the god, and see if he actually does come down there once a month. You could do that. But the problem, the first problem, is that to at least some extent the religions must be legitimate because of the Ascendants. Certain humans, when they die, come back. And they come back as sort of these almost Demigod-like figures. The followers of Genosus are called Paladins, and they have halos when they stand in direct sunlight. If they hit things that fit a certain qualification of evil, decided by their religion, the things just burst into flames.

Q: Did you say “Paladin” or “Paragon?”

Zach: Paladins.

James: Paladins, in a stereotypical D&D sense. The one difference is that they’re not serving “good” or “evil,” particularly. That’s not how they see it. I guess they see it like that, they see “actually, yeah, we’re the good guys!” But their powers are centered around what their god believes to be good. If Genosus says that left-handed people are evil, then a paladin can smite a left-handed guy and they would explode, regardless of whatever ethical argument you might make to the paladin. It’s more of a religious thing. On the other side, you have the Silver Guard, who are said to be the actual children of the goddess. Bocanadessia reincarnated the followers… her followers who are sufficiently good are reincarnated as demigods. I think they have ice powers, they can freeze things. They can mark people and make and cure disease. They’re supposed to be more of a mysterious, beautiful and distant, unknowable demigod as opposed to the Paladins being more of this superman, “God’s Personal Ass-stomping Machine” kind of demigods. Hercules versus… Orpheus? Yes, [a] Hercules versus Orpheus sort of thing.

Q: So if I wanted to be a wizard, and I wanted to work magic, how would that work? Would I be looked down upon by the gods? Would I have to keep from being burned at the stake as a warlock or something like that?

[chuckling]

James: If you’re deep in sun worshipper territory, you might want to hide all the moon tattoos. Pyromancy is more iffy. It would also depend on what country you’re in. The Kamens, which are sort of like Southern Germans, might not appreciate that so much. They might have a bad history with, quote-unquote “witches” or “firedancers,” and they might just try to kill you just because you might be a dark pyromancer. Or, if you practice sorcery, you might want to keep that quiet if in some country that was run by sorcerers until recently. There’s all sorts of stuff that could come up there. Generally speaking, every magic type has its niche except pyromancy. Dark pyromancers are just bad, no matter what.

Q: It sounds like, for the most part, the types of magic you have in the setting are not specifically inspired by any sort of occult groups that we’ve seen in the real world.

James: There’s some references, but it’s hard to explain those briefly. I put a lot of Kabbalistic references into some of the sorcery material, but that’s something that’s so obscure that it barely even counts.

Q: It makes sense too, because it’s not like they were actual magic to begin with. They were beliefs that people had, but there is, to date, no evidence any of it actually worked.

James: Yeah, yeah. You know, that’s the point. No matter what you believe, I’m pretty sure there are no Jewish wizards alive today shooting lasers out of their eyes.

Q: Which is a pity, because I might be able to do that, being half-Jewish.

[laughter]

Zach: You can shoot one. One laser out.

Q: Just my left eye!

James: You gotta go to special Kabbalah school for that stuff. They don’t teach you that at the lower levels. You have to put some time in.

Q: I’m one of those humanistic, non-religious Jews though, so…

Zach: No lasers for you then, I guess!

Q: Yeah, I guess I just have to be like Einstein [editor’s note: I wish!] or most of the entertainers you see and, you know, I’ve got that going for me, but no lasers.

[chuckling]

Q: What does ring true to me is that different cultures in-game react differently to different types of magic, just as how in the real world one man’s magic is another man’s—or woman’s—mystery religion. Especially when you have one religion replacing the other, even within the same tradition, you tend to cast the previous [faith] as being composed of sorcerers and necromancers and evil and that sort of thing. The new sorcerers, as it were, were the thaumaturges of order, to use your own terminology. [They were] people who were in touch with God, whatever they considered that to be. You can see this all over the world, but especially when you take a look at Biblical mythology: the whole myth of Exodus, which some scholars consider a metaphor for the [ancient] Hebrew people trying to break away from the cultural influence of Egypt. And of course all the Egyptian priests were, ah…

James: Portrayed as magicians…

Q: …and necromancers. Of course, Moses himself—he was just a prophet. That’s what he was. And you can see that in many different traditions around the world as well. Even in Greek mythology you often have similar issues, although the part I can remember clearly has to do with human sacrifice and not portraying the previous groups as witches and warlocks and whatnot. But it definitely seems like you have the same thing here. The patterns of history remain, even if the details are almost entirely different.

James: Yeah. That is what we were going for.

Watch for the third and final part of the interview this Friday. You may learn more about Song of Swords on its Kickstarter page, or back the project. The crowdfunding campaign will conclude on March 18th.

Zachary Irwin, also known as, Claymore, is President and co-founder of Opaque Industries. A former Chaosium employee, he boasts five years of experience in the game industry and collaborated with James Lacombe on the Song of Swords ruleset.

James Lacombe, known online as Jimmy Rome, is the lead game designer for Song of Swords and co-founder of Opaque Industries. He is the creative mind behind the setting of Vosca, and has refined the game through numerous online playtests.

Taylor Davis, or “Bones” as he is known online, was not able to join us, but is no less an important part of the Song of Swords team. A mobile gaming professional, he serves as art director and project manager, shaping the look of the game through collaboration with the art and layout teams.