Two weeks ago, I spoke with Zachary Irwin and James Lacombe of Opaque Industries about their upcoming tabletop fantasy roleplaying game Song of Swords. The game, which is being funded on Kickstarter is remarkable for its attention to history. Both its detailed combat system and the fantastical setting of draw heavily upon historical martial arts, culture and folklore. As attempting an accurate depiction of historical European fencing was one of my primary goals in Rosaria of Venice, I simply had to invite the team to speak on that, and other, subjects.

Zachary Irwin, also known as, Claymore, is President and co-founder of Opaque Industries. A former Chaosium employee, he boasts five years of experience in the game industry and collaborated with James Lacombe on the Song of Swords ruleset.

James Lacombe, known online as Jimmy Rome, is the lead game designer for Song of Swords and co-founder of Opaque Industries. He is the creative mind behind the setting of Vosca, and has refined the game through numerous online playtests.

Taylor Davis, or “Bones” as he is known online, was not able to join us, but is no less an important part of the Song of Swords team. A mobile gaming professional, he serves as art director and project manager, shaping the look of the game through collaboration with the art and layout teams.

What follows is the first of three parts to our conversation. The transcript has been edited for clarity and length, and occasionally for accuracy.

Q: What is song of swords? Pitch the game to me.

Zach: Song of Swords is a tabletop roleplaying game that is gritty, dark, low fantasy or historical. We have a focus on realistic medieval combat. All of the arms and armor in our game are based on reality, and based upon whatever research we can do. We also have a very strong narrative focus. So, basically, you don’t need to cleave through an army of goblins to level up early. You follow who your character is, and advance them that way.

Q: What do you mean by low fantasy? What defines that, specifically?

Zach: A good example of [low fantasy] would be earlier Game of Thrones. It’s less like Forgotten Realms and Dungeons and Dragons, where wizards flying through the sky and throwing fire bolts is commonplace.

Q: So low fantasy, if you’re talking about Game of Thrones, is like the parts of Game of Thrones in which the most significant things happening is everyone being incestuous and killing each other, before the elves and…

Zach: Dire wolves and dragons and elves, yeah.

Q: Got it.

James: “Low fantasy” is what we’ve settled on, but it would be very misleading to say that this is a purely no magic [setting]—knights and political intrigue exclusively thing. The official setting is one where you have flying islands, dragons made out of bronze and crystal, shooting radiation out of their eyes… I guess when we say “low fantasy,” what we mean is that the focus of the game is always very much on the personal interaction between characters and things that are grounded in reality. It’s easy to understand hitting someone in the neck with a sword. That’s very visceral, it’s something that’s easy to wrap your mind around. Magic is something more nebulous. By its nature, it’s mysterious. So the more focus you put on these magic elements that require a suspension of disbelief and kind of a distancing from reality, the higher I feel your fantasy is.

Q: I see. So you have all of this ridiculous, fantastical stuff in there, but that’s not the entry point. Whereas [with] a lot of fantasy, the entire appeal is to get in there and say “Oh! I’m a wizard! I’m going to throw fireballs all over the place—” you’re starting with the mundane, so when you encounter the magic it is more mysterious, more powerful when you actually encounter it. Would that be correct?

James: Precisely. We should come up with a new term for that. We should call it “inclined fantasy.”

[laughter]

Zach: “Sliding scale” fantasy?

Q: “Inclined fantasy,” I can see that. You have to work your way up to it, just like everything else.

James: The staircase to the dark fantasy.

Q: So, comparing and contrasting this with, say, Dungeons and Dragons, which is what one might think of as the industry standard when you mention “tabletop RPG.”

Zach: Now, I’d say that’s Pathfinder.

[laughter]

Zach: Nah, Dungeons and Dragons of course.

Q: That’s essentially, what, D&D 3.815 now?

Zach: 3.75.

Q: Overall, how does Song of Swords differ mechanically from D&D? What are the differences between playing your standard RPG and playing a game of Song of Swords?

Zach: What we have here is called the “Arc System.” When a character is being made, they fill a few slots on the character sheet. The first is the Saga slot. That is shared by the entire group, and that is supposed to represent the core storyline of the campaign. It is what the GM is running. Whenever they reach milestones in that, they basically gain experience points through that avenue. After that, they have the Epic Slot, which is that character’s overall story. Such as: Tom is trying to find his wife, who was stolen by bad guys, or someone’s trying to avenge a father—something along those lines. Something personal to the character.

Q: So, it’s almost something like what White Wolf does with their games, where you incorporate the roleplaying into the character creation process.

Zach: Exactly.

Q: Instead of just having the flavor, it’s part of the character system.

Zach: Yes, we want to directly reward following those goals. Beyond that, we also have Belief and Glory, which are two other ways the characters can see what they value and reward it with experience inside the systems.

Q: Is it just a way of rewarding characters and players with experience, or does it actually affect the characters’ abilities to some extent?

Zach: This is the core way they gain experience. And they take that experience and use it to level up the way they want to within that system.

Q: So it encourages them to roleplay, instead of just mucking around…

Zach: Well, beyond that, it encourages them to pursue their goals.

Q: So when they get experience that’s when they get the nifty sword, nifty ability…

Zach: They get a little stronger, or learn a new maneuver.

James: To get back to the original question of how the beginning of a Song of Swords game differs fundamentally from D&D… in D&D, the first thing you try to do is try to find something like a goblin, or kobolds or whatever—you’re hunting rats or something like that—you start gathering experience so you can climb out of the pit that is low-level D&D. You want to get to level two, so you kill some goblins. You find some orcs, and you kill them. It’s a long chain of monsters that you climb like a ladder. With Song of Swords, your venue for getting stronger as a character—there are no levels so it’s not that codified—but the venue or the path to improving the character is not by just finding things and killing them. It’s detached from that entirely, in fact. If your arcs have nothing to do with violence, you can be killing goblins for twenty years and not get any stronger. You get stronger by doing what your character would do if this were a story being told, by following the arc of the story, and most importantly by following the plot of the campaign itself. The group is very motivated not to branch off and do their own thing, or to procrastinate too much. This sense of progress is supported mechanically as you move forward narratively in the campaign.

Q: So how has that actually worked out? What sort of feedback have you gotten when people run the game?

James: Well I think it’s worked out pretty well so far. We’ve had some mixed reports. Some people liked it, some people didn’t if they came from a very different system. By and large, the response has been that it works well. It’s a good system, it keeps people focused. If you came to this from Dungeons and Dragons, you’re kind of expecting a familiar milieu where… “Okay, so where’s the dungeon we’re going to? Where’s the dungeon, there’s going to be a dragon at the end of it, right?” That’s how it always is, right?

Q: Yep.

James: But it isn’t always like that in Song of Swords. Instead you’re delivering a message to a bishop. How do we fight a dragon if we’re delivering a message to a bishop? The point is, you’re not fighting a dragon—yet. The bishop is the quest for now. It tends to be more of an above-ground, character-oriented story that emerges, though there’s certainly room for treasure hunts and Conan the Barbarian-esque ancient riches plundered from tombs, and all that good stuff. The feedback we’ve gotten primarily suggests to us that it is working. The system does work and people do like it once they get used to it.

Q: It seems like it’s mostly a matter of taste. If people are expecting D&D, then they might be a little confused. But if they go along with, it seems people end up enjoying it at the end.

Zach: Definitely so.

Q: One of the main distinctions you make between Song of Swords and other RPGs is how you handle combat. Now Zach, I understand you have a grounding in Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) and swordplay.

Zach: Somewhat, yeah.

Q: So, tell me how actual fights, to your knowledge, compare to what you’d see in an RPG.

Zach: People always tell those jokes, you know, [that] in Final Fantasy you’re waiting to hit each other and everything like that, so…

[laughter]

Zach: I mean, that’s true for most games. So we try to move away from that a little bit. We try to follow reality, in that it’s not just waiting for your turn. You have options to steal the initiative, or do your attack when you want to, and things like that. James’ll give you a bit of a better overview, but I do want to tell one story, real quick, that Taylor likes to tell a lot. He was sitting down to play Dungeons and Dragons with us for the first time, and I can’t remember—I think we were fighting a purple worm or something—and he said: “Okay, I want to stab it in the eye!” “So, well, you can’t do that.” “So why can’t I stab it in the eye?”

[laughter]

Zach: And so that little split in reality is something that drove us a lot in making the game. We want to give people the option to follow reality, and to logically think about what they want to do, instead of just looking inside the rules and making all of the decisions based off of that.

Q: So the idea is to take the rules and provide a framework for people to do what they want with them, rather than using them to limit their options of what you can do.

Zach: Yeah, we want them to think of it logically and [realistically].

James: Taylor and Zach tend to focus very much on the options and the choice this kind of thing provides to players, and that’s a legitimate thing. It’s good to have options, and it’s good to be able to feel like you have a good idea, like “I’ll bet you this guy’s legs are unarmored. Attack his legs, because he’s wearing the helmet and has the armor; that’ll be more effective.” And it’s fun to see that rewarded. The direction I was coming from was more a love of history. I’m very much into historical warfare and historical martial arts, and I went through a lot of trouble, as we were making this game, to follow in the footsteps of older historians. I read George Silver’s Paradoxes of Defense. It was written five hundred years ago, and it’s this English guy…

Q: He was an English swordsman, right?

James: Yeah, yeah George Silver. You’ve probably read him too.

Q: I haven’t read him, but I’ve done a little bit of HEMA. So yes, I’ve heard of him.

James: He was very famous for being critical of rapiers. He didn’t like rapiers. I thought he was a little too critical.

[chuckling]

James: But he wrote a book called “The Paradoxes of Defence,” or something. [And there was also] Paulus Hector Heir[,] a German guy who embezzled a bunch of money so he could make these really, really beautiful detailed fechtbooks which detailed the martial arts of the day. It’s one of the reasons we know a lot about martial arts. Eventually he got caught embezzling all that money and they hanged him.

[laughter]

James: But his books survived. The fechtbooks survived. So now we know Germans used to fence with agricultural scythes. No joke. They actually have illustrations and everything.

Q: So apparently there’s European kempo as well as Japanese kempo.

James: There’s a lot more of it than a lot of people think. It’s starting to become mainstream now. If you’ve heard of video games like For Honor—one of the guys behind that was pretty big into HEMA. Of course not everything would be perfectly realistic. If you look on the Internet, there’s just thousands of videos talking about stuff that’s not quite realistic enough in For Honor, as though a game with Vikings and Samurai fighting knights was supposed to be realistic.

[laughter]

James: I think that some people are a little too quick to jump on that train, but the point is at least they were trying. And when you see stuff, like a guy holding a sword by the blade to beat a dude with the handle—that was totally real. That was a mordhau, or a “murder strike” in [English], and you can do it in our game. It’s a real technique back in [Renaissance] Germany. I think we have a good trio here, where Taylor really likes the idea of giving more options in combat, Zach really likes the idea of agency and the realism of it. I just really like being able to read through these ancient books, and try to bring something of the historical elements of combat to the modern game, because it’s also very interesting to write systems for. It’s crazy hard, but it’s very fun.

Q: How do you translate those historical techniques from George Silver, or Swetnam or Capo Ferro, into a game where people don’t necessarily know everything about Historical European Martial Arts, or any sort of martial arts to begin with? How do you translate that in a way that makes it intuitive for your average gamer?

James: Well, I’ll tell you this: you have to lay off, very early, the idea of naming moves after their historical equivalents. It does not help anyone at all to say that “Yes! I’ll do a mandritto fendente!” You’re like: “What the hell is that?” Half the treatises are in Italian, the other half are in German—it just doesn’t help. We’re not going too far into modeling specific strikes and their historical names, but we’re making sure that you can do everything, or just about everything, that was shown in these historical manuals. So if you know a lot about historical martial arts, then you can make a character and play it in an exactly realistic way, just about. We have a few people in our fan base who are very into this thing, and they sometimes limit themselves to realistic moves only, which is pretty fun. But if you’re not an expert in, you know, 15th century German poleaxe or something, you don’t have to go too far into that. I can say ‘I just want to bash him in the head’, roll dice—and that works just as well.

Q: So you’re allowing the players to set how realistic it is.

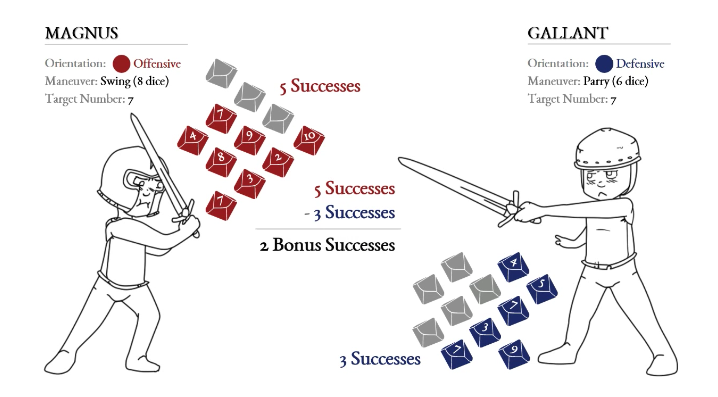

Zach: Definitely by the campaign group. Though, as far as complexity goes, our moves are really split into just two or three different categories. It’s swing, stab, and that’s pretty much it.

James: You can do stuff like counters, or a murder strike where you bash someone with the hilt. That would be considered a swing, but it’d be a subcategory. When you boil it down to the absolute basics, you can parry, strike, thrust, or block with a shield. And then you can dodge, too. There are advanced maneuvers that come out if you need to do something very specific, but a lot of the time you can play through most of the game without having to do anything clever like that, and it’s just as exciting.

Q: So, say if I’m doing something like a murder stroke, taking the blade in two hands and striking someone over the head with it, do you have to stat that out? The longsword, technically speaking, can be used as something like five different weapons. You can use it as a sword, use it as a pick if you hold it by the blade, or you can use the pommel as something like a hammer, or as a dagger if you half-sword. Do you have to stat all that out, or do you have a way to just wing those sorts of maneuvers so you don’t have to have everything statted out ahead of time?

James: This is a problem we ran into early, which is if you let them do it with one weapon, they’ll probably do it with others that you aren’t expecting. So we just had to sort of accept that was a thing. You… there’s a little formula in the maneuvers, so if you want to do a murder strike you just look at “Murder Strike” and it says: “okay, so now your weapon does -2 damage, but the damage is bludgeoning.” Or something like that.

Q: So you did have to make specific techniques sometimes?

James: We made specific techniques for just about everything. It’s just they follow the same general formula as the major techniques, so it wouldn’t get too confusing. The problem, of course, is that you could then theoretically do a murder strike with a rapier. You know, you could grab the rapier by the blade and then swing it like a ridiculously thin-handled club.

Q: Yeah, which wouldn’t work very well with a rapier.

James: Yeah, that wouldn’t be realistic at all. If the players want to do it, and they have no shame, then whatever.

Q: So, technically speaking, I guess that means you have your basic attacks, and you have maneuvers, and the maneuvers are variants on basic attacks?

James: Basically. They’re all technically maneuvers, but you have basic attacks, and then advanced attacks, and they’re just a subset of those. We really don’t have a consistent terminology just yet. There are a couple of maneuvers that don’t follow any formula, or they don’t follow the original formula, like—what do you call it? Binding. We call it “hilt push.” It’s when the swords are physically contacting each other and you sort of weave and try to maneuver around the opponent’s weapon to get at them. You’ve seen that—I’m sure—in movies and things like that, where the two guys just get their swords together and [push]. It’s a little bit Hollywood, but it did happen historically. Of course, it’s very hard to model rules for. [There’s] also grappling. You have to have rules to suplex people. It’s not medieval combat unless you have two guys in armor suplexing each other.

Zach: It really does just start off with cut or thrust, and then a block or a parry. That’s as simple as it is for new players. As they play it more, and they read more, they start to understand the more advanced maneuvers. And their characters get a little stronger, and they try out a murder stroke once, or something like that.

Q: Do some of these maneuvers only become available once you level your character up?

Zach: It really depends upon how you build them at the start, because people can, depending on how powerful of a campaign they start out with, start out kind of high in some areas and low in others. Or they can be a balanced character. We break everything into its own category. You have a certain amount of points to kind of sprinkle around where you want to.

James: Yeah. Between proficiencies, which would be like weapons skill, and then your social class [and so on]. So you could, theoretically, just start the game with a very high combat proficiency. But generally you have to level up your combat proficiencies before you gain access to high-tier maneuvers. The really high level stuff lets you parry and attack at the same time, with the same weapon.

Q: So it’s just like learning a martial art, where first you learn the basic moves, and then the more complicated ones, and how to apply the basics.

Zach: And again, we wanted it to follow reality. [laughs]

Q: I see. Going back to what you said about For Honor: the game is more realistic than most in how it portrays combat. I’m not too familiar with it, but I’ve heard of [the game] and it seems like they pay more attention to historical origins of these martial arts. It’s still purely fantasy because they’re mixing and matching time periods. But there’s always a bit of a flight of fancy when you’re doing a fantasy game. That’s part of the appeal: that you’re also doing things that you can’t do in reality. How do you incorporate that into your combat system?

James: It depends on what you mean, exactly. Because our repertoire is so broad right now in terms of weapons and armor, you can have match-ups that wouldn’t have occurred historically or that are very unlikely to have occurred historically. So, if you want to see a guy—a Samurai from the Sengoku Era—fight a fourteenth century knight, you can do that. You can have that match. You can make those characters, and you can see how that would pan out. That was a big pastime of people in the fan base early in the game’s development. They really wanted to do “The Deadliest Warrior” thing. They were like: “Okay, so I wanna see how an Aztec warrior would do against a Roman legionary.” And they would slap those two guys together and have them fight it out.

Q: Nice.

James: But another thing is, because it is a fantasy game, it’s actually plausible that, in the course of play, you could run into stuff that wouldn’t happen or that would be very unlikely to occur in reality. Or would be impossible. Magical weapons—that’s not something you have in the real world, as far as I know. I’ve heard legends, but I’m [doubtful]. But imagine how terrifying it would be to fight someone who actually had a flaming sword. I mean—think about that. It’s horrible. Even if you parried, it’s still on fire. Fire doesn’t stop moving. You’d get your hair lit on fire. It’d be really unpleasant to fight someone with a flaming sword. Well, thankfully it’s not something you have to deal with in the real world, but on the swords [in the game] you can have… swords that cut through anything, or spears that…

Zach: Change length, or extend.

Q: It seems like, until you get to the magical parts, the characters themselves have abilities that generally correspond to realistic levels of strength, speed, agility…

Zach: Generally, yeah. The place where we do play with that a little bit are in the different races the players can play. That’s another area where you can invest at character creation; you can play an Elf, a Dwarf, or a Goblin, or a Star Vampire…

[chuckling]

Zach: …you know? There’s some different races.

James: I love it that someone has to say “Star Vampire.”

Zach: Yes.

James: That’s great. It just makes me all warm and fuzzy inside. And one of the things you’ll notice there is that because you have to devote points to that, the races are not equal. There’s no pretense of that. One of these powerful, immortal elf-things is just superior to a human. And that’s what you would expect. But in a lot of fantasy games, you don’t get that. A first-level human and a first-level elf are exactly the same, basically, even though the elf is 200 years old.

Q: Makes sense.

James: And the human is 20, or 14, you know?

[chuckling]

James: That struck me as a little bit ridiculous.

Zach: You’re an adult at 13, right?

James: You can very much tell the difference between a Ohanedin and a human. An Ohanedin can put his hand through armor, if he has to.

Q: Wow. So it sounds like you can be those more powerful races, but you don’t get as many skills if you do.

James: Yeah. That’s true.

Q: Got it.

James: Yeah. So it’s just another [category] you invest in.

Watch for Part II of the interview this Wednesday. You may learn more about Song of Swords or back the project on its Kickstarter page.

This post was edited at 3:38PM on Monday, March 6th. Zachary Irwin’s title has been corrected from “CEO” to “President.”